The Rich Tapestry of Urdu: Scholarly Journey of Naqvi

Urdu literature, denoted as “Adbiyāt-i Urdū” in Urdu script, represents the literary works produced in the Urdu standard of the Hindustani language. Though predominantly inclined towards poetry, particularly the Ghazal (غزل) and Nazm (نظم) verse forms, it encompasses diverse genres, including the art of storytelling known as Afsana (افسانہ).

The influence and popularity of Urdu literature extend notably across Pakistan, where Urdu holds the status of a national language, and where it is recognized as a significant language.

Unraveling the Origins of Urdu Literature

The origin of Urdu literature intertwines with the cultural evolution of the Indian subcontinent. Rooted in the rich traditions of Urdu’s literary heritage has flourished over time, assimilating influences from various linguistic and cultural sources. While poetry, especially the ghazal, and Nazm, remains at the heart of Urdu literary expression, the form has diversified, embracing other literary styles, including the evocative narrative of the short story, the afsana.

This literary tapestry is an integral part of the broader Indian literary landscape, showcasing its distinctive linguistic and cultural identity within the realm of South Asian literature.

Urdu’s roots can be traced back to the 11th-century Muslim invasions of Punjab from Central Asia, although the language wasn’t known as “Urdu” during that period. The emergence of Urdu literature occurred around the 14th century in what is now North India, primarily among the cultured elite in the courts. The influence of Islam and the support for foreign cultural practices by earlier Muslim rulers, often of Turkic or Afghan descent, significantly shaped the Urdu language. This influence persisted due to the prevalence of both cultural heritages across Urdu-speaking regions, leading to a linguistic amalgamation characterized by a vocabulary that drew from Sanskrit-derived Prakrit and Arabo-Persian words.

The Flourishing Epochs: Deccan Influence and Mughal Patronage

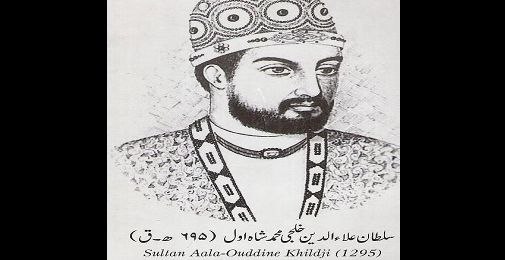

During the religious period spanning from 1350 to 1590, Urdu literary compositions took shape, initially in the Deccan region during the 14th century. The soldiers of Alauddin Khalji, who raided the Deccan between 1294 and 1311, introduced an early form of Urdu in that area. Subsequently, under the rule of Muhammad bin Tughluq, who shifted the capital from Delhi to the Deccan in 1326, and later with Zafar Khan’s establishment of the Bahmani Sultanate in 1347, Urdu gained prominence in the kingdom, replacing Persian as the court language used during the Delhi Sultanate.

The variant of Urdu spoken in the Deccan, influenced by local languages like Gujarati and Marathi, was termed Dakhini. During this time, literary works, predominantly religious, were composed in Dakhini prose and poetry. Noteworthy writers of this period include Bande Nawaz, known for his Sufi tract “Miraj ul Asiquin,” which stands as one of the earliest examples of Urdu prose. Additionally, writers like Shah Miranji and his son Shah Buran contributed significantly to the literary landscape with their works.

In the Deccan region from 1590 to 1730, Urdu literature experienced significant growth. During the Qutub Shahi dynasty’s reign in Golkonda, Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah, the fifth sultan and founder of Hyderabad, stood out as a royal poet and prolific writer in both Persian and Dakhini, the regional variant of Urdu. Poets like Wajhi and Gavvasi also contributed to the literary landscape. Noteworthy works during this era include Ibn e Nishati’s “Phul ban,” a romance comprising 1300 lines, and Tab’i’s “Qissa o bairam e Gul andman,” a substantial work of nearly 2700 lines penned in 1670.

In the Adil Shahi period, Ibrahim Adil Shah II, another royal poet and a patron of arts and literature, produced “Kitab-e-Navras” in Dakhani, a collection consisting of 59 poems and 17 couplets. Poets such as Rustami, Nusrati, and Mirza also made significant contributions to the literary scene.

During the Mughal rule over the Deccan from 1687 to 1730, Wali Mohammed Wali emerged as a prominent Urdu writer, leaving a lasting impact on Urdu literature.

The 18th century marked the onset of the first Urdu literary period in Delhi, spanning from 1730 to 1830

Ghulam Hamdani Mas’hafi is credited as the first to coin the term “Urdu” around 1780 AD for a language that had various names before his time.

Transition and Transition: The Delhi Court to Contemporary Realities

In the 18th century, three significant forms of Urdu poetry gained prominence: ghazal, qasida, and masnavi. Poet Shaikh Zahuruddin Hatim, notable in Delhi during this era, left a legacy with works like “Diwan” and “Diwanzada.” Mazhar, Sauda, Mir, and Dard became pivotal figures, earning the title “the Four Pillars of Urdu Poetry.” Mir Hasan also made an impact with renowned masnavis, including “Sihar-ul-Bayan,” commonly known as “Masnavi e Mir Hasan.”

Among the important poets were Mas’hafi, Insha, and Nazeer during this period.

By the 19th century, the center of Urdu literature transitioned from Delhi to places like Hyderabad, Patna, and Lucknow. The Lucknow court emerged as a literary hub, attracting poets from Delhi, including Khaliq, Zamir, Aatish, Nasikh, Anis, and Dabir.

The second quarter of the 19th century witnessed the revival of Urdu poetry in Delhi’s Mughal court. Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last Mughal Emperor, was a poet and patron of poetry. Poets like Zauq, Ghalib, Azurda, and Momin flourished under his support and encouragement.

Some of Momin’s pupils in poetry, including Shefta and Mir Hussain Taskin, rose to become distinguished poets themselves.

The decline of the Mughal empire and the Awadh kingdom post the Rebellion of 1857, alongside increased interaction with the English language, triggered a fresh wave in Urdu literature. Notable figures of this era were Syed Ahmad Khan, Muhammad Husain Azad, and Altaf Hussain Hali. This period witnessed a surge in prose, criticism, and drama within Urdu literature. Writers and poets began exploring new themes, experimenting with different forms.

Altaf Hussain Hali, a prolific poet, left behind a vast body of work, including major poetic works like Masnavis, Musaddas e Hali, Shikwa e Hind, and Qasida e Ghyasia. He also penned marsias or elegies honoring the deaths of Ghalib, Hakim Mahmud Khan, and Sir Syed.

Suroor Jahanabadi was another advocate of the new movement in Urdu poetry. His patriotic poems such as Khak-i-Watan (The Dust of the Motherland), Urus-i-Hubbi-Watan (The Bride of the Love of the Country), and Madar-i-Hind (Mother India) gained recognition. His historical and religious compositions like Padmani, Padmani-ki-Chita (Funeral Pyre of Padmani), and Sitaji-ki-Giria-o-Zari (The Laments of Sita) showcased his diverse writing skills.

Ghalib, renowned for his poetry, also contributed significantly to Urdu prose. His collection of letters and three short pamphlets, namely Lataif-i-Ghalib, Tegh-i-Tez, and Nama-i-Ghalib, reflected his versatility. His autobiographical letters were compiled into two volumes known as Urdu-i-Mualla (the Royal Urdu) and Ud-i-Hindi (Fragrant Stick of India).

Before the 19th century, Persian served as the official language in courts and cultural exchanges. The emergence of Urdu prose for practical purposes can be traced back to the establishment of Fort William College in Calcutta in 1800. John Gilchrist, the head of the college, authored several Hindustani works and assembled a group of Indian scholars. These scholars, including Mir Amman Dehelvi, Mir Sher Ali Jaafri, and others, contributed significantly to the development of Urdu prose.

Syed Ahmed Khan, a prominent figure in the Aligarh Movement, was a prolific writer covering a range of subjects from theology to history. His notable theological work, Al-Khutbat al-Ahmadiya fi’l Arab wa’I Sirat al-Muhammadiya, published in 1876, and his contributions to Urdu journalism through journals like Tehzeeb-ul-Akhlaq and the Aligarh Institute Gazette, underscored his influential literary legacy.

The Aligarh movement cultivated a group of literary enthusiasts whose impact on Urdu literature extended far and wide. Among them, Shibli Nomani and Zakaullah Dehlvi stood out for their historical and literary contributions. Nomani, often hailed as the pioneer of modern history in Urdu, penned several biographical and historical works, including Sirat-un-Nabi, Al-Farooq, Al-Ghazali, and a notable travelogue titled Safar Nama e Rome-o-Misr-o-Sham, chronicling his travels abroad.

Zakaullah Dehlvi‘s monumental work, Tarikh-e-Hindustan, spanning fourteen volumes, was a significant achievement in Indian history written in Urdu.

Altaf Hussain Hali, recognized for his poetry, also made substantial contributions to Urdu prose. Notable among his prose works are biographies like Hayat-i Saadi and Hayat-i Javed, alongside Yadgar-e-Ghalib, which focused on the life and critical analysis of Ghalib.

Urdu literature saw the emergence of its first original novel, Mirat-ul-Uroos, in 1869, written by Nazir Ahmad Dehlvi. This novel served as conduct literature, particularly about marriage, followed by other conduct books like Binat-un-Nash and Toba tun Nasoh.

Muhammad Husain Azad laid the groundwork for historical novels in Urdu with works like Qisas ul-hind and Darbār-e akbarī. His Aab-e hayat stands as the initial chronological history of Urdu poetry from Wali to Ghalib.

Ratan Nath Dhar Sarshar introduced proper fiction and elements of realism in Urdu novels through his serialized novel Fasana-e-Azad, influenced by Don Quixote. His other notable works include Sair-i-Kohsar and Jam-i-Sarshar, and he contributed articles and short stories to the humorous journal, Awadh Punch.

Inspired by the historical romances of Walter Scott, Abdul Halim Sharar introduced historical elements in his writings, evident in works like Malikul Azia Vārjina.

Mirza Hadi Ruswa, known as a poet and writer, is best remembered for Umrao Jaan Ada, a significant literary work published towards the end of the nineteenth century

In the 19th century, Urdu drama began through Agha Hasan Amanat’s “Inder Sabha,” which premiered in 1853. This musical comedy, resembling European opera, boasted a light plot.

Winds of Change: The Progressive Writers’ Movement and Modernist Era

Moving into the 20th century, the prose saw significant developments. Premchand, an influential figure in Urdu literature, emerged in the early 1890s, contributing substantially to both Urdu and Hindi literature. His works covered diverse themes such as religious and social reforms, the plight of various societal classes, and pioneering European-style short stories. However, his first collection of short stories, “Soz-e-Watan,” published in 1907, faced a ban by the British government.

During this period, other noteworthy writers included Sudarshan, Mohammad Mehdi Taskeen, Qazi Abdul Gaffar, Majnun Gorakhpuri, Niaz Fatehpuri, Krishan Prasad Kaul, and L.M. Ahmed.

The 1930s marked a significant shift where the short story gained prominence, influenced by Western styles, especially English, French, and Russian literature. The “Angarey” collection, published in 1932 by Sajjad Zaheer, Rashid Jahan, Mahmud-uz-Zafar, and Ahmed Ali, heralded the Progressive Writers’ Movement. This movement profoundly impacted Urdu literature for about two decades.

Ismat Chughtai, a prominent progressive writer, focused extensively on feminine themes in her novels and short stories, notably in collections like “Kaliyan” and “Chotein.” Her work “Lihaaf,” published in 1942, remains a memorable short story.

Krishan Chander provided a realistic portrayal of life in his novels and stories, addressing social issues and human experiences in works like “Ek Gadhe ki Sargushisht,” “Shikast,” “Zindagi ke Mor Par,” “Hum Waishi Hain,” “Anna Datta,” “Kalu Bhangi,” and “Paude.”

Saadat Hasan Manto, another significant writer of the era, created intricately crafted stories such as “Khol do,” “Toba Tek Singh,” “Mozelle,” and “Thanda Gosht.”

Amir Khusro wielded significant influence not only on the early evolution of Urdu literature but also on the language itself, which began to take a distinct form around the 14th century, diverging from both Persian and proto-Hindi. Credited with organizing northern Indian classical music, including Hindustani music, Khusro wrote in Persian and Hindavi. Although his couplets reflect a later Prakrit Hindi sans Arabo-Persian vocabulary, his impact on court viziers and writers was profound. A century following his demise, Quli Qutub Shah conversed in a language akin to what could be termed Urdu. Sultan Muhammed Quli Qutb Shah, proficient in Persian, Arabic, and Telugu, authored poetry in these languages. His poetic collection, “Kulliyat-e-Quli Qutub Shah,” encapsulates his contributions. Recognized as the first Saheb-e-dewan Urdu poet, his influence transformed prevailing genres of Persian/Urdu poetry and was pivotal in elevating Urdu to a literary status. His demise occurred in 1611.

Sayyid Shamsullah Qadri holds the distinction of being considered the foremost researcher of Deccaniyat. Among his notable works are “Salateen e Muabber 1929,” “Urdu-i-Qadim 1930,” “Tareekh E Maleebaar,” “Mowarrikheen E Hind,” “Tahfat al Mujahidin 1931,” “Imadiya,” “Nizam Ut Tawareekh,” “Tareekh Zuban Urdu-Urdu-E-Qadeem,” “Tareekh Zuban Urdu Al Musamma Ba Urdu-E-Qadeem,” “Tareekh Zuban Urdu Yaani Urdu-E-Qadeem,” “Tarikh Vol III,” “Asaarul Karaam,” “Tarikh,” “Shijrah Asifiya,” “Ahleyaar,” and “Pracina Malabar.”

Urdu literature, predominantly poetic, also encompasses the realm of prose, notably in the form of epics known as “dastans.” These tales, originating from the Middle East and disseminated by oral storytellers, weave intricate narratives involving magical elements and unbelievable events. Reflective of folklore and classical literary themes, dastans share similarities with various narrative genres in Eastern literature like Persian Malawi and Punjabi Qissa and even evoke elements akin to the European novel.

The oldest known Urdu dastans include Dastan-i-Amir Hamza, from the early 17th century, and Bustan-i Khayal (The Garden of Imagination) by Mir Taqi Khayal (d. 1760). Notably, most narrative dastans were recorded in the early 19th century, borrowing motifs from Middle Eastern, Central Asian, and Northern Indian folklore. Prominent dastans include Bagh-o-Bahar (The Garden and Spring) by Mir Amman, Mazhab-i-Ishq (The Religion of Love) by Nihalchand Lahori, and Araish-i-Mahfil (The Adornment of the Assembly) by Hyderbakhsh Hyderi.

Tazkiras, or literary memoir compilations, contain verses, maxims, and biographical details of poets, offering insights into their styles and compositions. These collections often present poets’ names with brief information about their works, although larger anthologies don’t systematically review the poets’ entire repertoire.

Urdu poetry, reaching its zenith in the 19th century, finds its most refined expression in the ghazal form, renowned for its depth and breadth within the Urdu tradition. Additionally, poets influenced by European languages, particularly English, began crafting sonnets in Urdu during the early 20th century. Figures like Azmatullah Khan and others contributed to the introduction and cultivation of this format within Urdu poetry.

Initially, Urdu novels predominantly centered around urban social life but gradually expanded to encompass rural settings. The literature evolved, particularly under the progressive writing movement sparked by Sajjad Zaheer, examining the changing societal landscapes. However, the partition of India significantly influenced the genre, delving into themes of identity and migration, evident in the notable works of Abdullah Hussain and Quratul Ain Haider.

As time progressed, Urdu novels began to shift focus towards contemporary life, especially addressing the realities faced by the younger generation in India. Notable novels from this period include “Makaan” by Paigham Afaqui, “Do Gaz Zameen” by Abdus Samad, and “Pani” by Ghazanfer. These works steered away from prevailing themes of partition and identity issues, diving into modern-day realities and life in India. “Makaan,” in particular, had a far-reaching impact, influencing English writers such as Vikram Seth, who ventured into novel writing.

Later novels like “Andhere Pag” by Sarwat Khan, “Numberdar Ka Neela” by S M Ashraf, and “Fire Area” by Ilyas Ahmed Gaddi were also influenced by these Urdu novels. Paigham Afaqui’s “Paleeta,” published in 2011, portrays the political disillusionment of an ordinary Indian citizen over six decades post-India’s independence, depicting a society transformed into a mental desert. This novel ends with the central character’s writings catching fire after his demise.

Numerous Urdu novels have left a lasting impact on the literary landscape. “Mirat-ul-Uroos” by Deputy Nazeer Ahmed, “Umrao Jaan Ada” by Mirza Hadi Ruswa, and “Aag Ka Darya” by Quratulain Haider are hailed as pivotal works. These novels, covering themes of women’s education, moral values, and life’s vicissitudes, have earned significant acclaim and even been translated into multiple languages. Additionally, contemporary novelists like Rahman Abbas have emerged as influential figures, challenging established beliefs and elevating storytelling to new heights.

Urdu literature has embraced the short story form for over a century, traversing various phases from romanticism to social criticism. The genre solidified with the prolific works of Munshi Premchand, known for notable stories like “Kafan” and “Poos Ki Raat.” The Urdu short story gained significant traction with the groundbreaking publication of “Angare,” a collection that highlighted several writers towards the end of Premchand’s era. Writers like Ghulam Abbas, Manto, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Krishan Chander, and Ismat Chughtai further elevated the short story into a prominent genre within Urdu literature.

Subsequently, the next generation of Urdu short story writers included names like Qurratulain Hyder, Qazi Abdul Sattar, and Joginder Paul. This tradition endures with younger writers such as Zahida Hina, Paigham Afaqui, and Syed Muhammad Ashraf, as well as notable female authors like Afra Bukhari and Wajida Tabassum. These stories have delved into a spectrum of life’s dimensions, notably addressing the aftermath of the subcontinent’s partition and the ensuing violence. Towards the end of the last century, short stories have delved deeply into the complexities of daily life, evident in Paigham Afaqui’s “Mafia,” Moinuddin Jinabade’s “T’abir,” and Nayyer Masood’s “Taus Chaman Ka Maina.”

Urdu drama traces its roots from the dramatic traditions of North India, particularly under exponents like Nawab Wajid Ali Shah of Awadh, and later evolved into Parsi Theatre. Agha Hashr Kashmiri marks the pinnacle of this tradition. The impact of Urdu theater extends to modern Indian theatre, remaining popular alongside languages like Gujarati, Marathi, and Bengali. Classic playwrights include Prof Hasan, Ghulam Jeelani, J. N. Kaushal, Shameem Hanfi, and Jameel Shaidayi. Post-modern playwrights such as Danish Iqbal, Sayeed Alam, Shahid Anwar, Iqbal Niyazi, and Anwar are actively contributing to Urdu drama, employing newer techniques and contemporary perspectives. Sayeed Alam, Danish Iqbal, and Shahid are known for their distinctive plays reflecting modern social realities rather than being purely academic, further enriching the performing tradition.

The landscape of Urdu literature has been shaped by several significant literary movements.

The Progressive Writers Movement considered one of the most robust movements after Sir Syed’s educational initiative, profoundly impacted Urdu literature. It emphasized social change and justice, showcasing the struggles of the common person.

Around the 1960s, the modernist movement emerged, focusing on symbolic and indirect expressions rather than direct ones. Key figures like Shamsur Rehman Farooqui, Gopichand Narang, Noon Meem Rashid, Meeraji, Zafer Iqbal, Nasir Kazmi, Bashir Bader, and Shahryar were associated with this movement, exploring innovative ways of literary expression.

Halqa e Arbab e Zauq, inaugurated in Lahore in 1939, was another influential movement, following closely after the Progressive Writers’ Movement. Featuring prominent poets like Noon Meem Rashid, Zia Jallandhari, Muhtar Siddiqui, Hafeez Hoshiarpuri, and Meeraji, it wielded considerable influence on modern Urdu poetry.

Post-modernism, introduced by Gopi Chand Narang, ushered in a fresh approach to literary criticism. Unlike a movement, it didn’t advocate a particular style but focused on interpreting contemporary literature, examining diverse elements like feminism, Dalit perspectives, regionalism, and other themes to comprehend the richness and variety of global literature.

As the 1980s concluded, Urdu literature witnessed a shift. The Progressive movement was dwindling, and the modernist movement seemed to exhaust its innovative spirit. However, this period also saw the emergence of independent writers like Paigham Afaqui, who brought in a new wave of creativity. Afaqui and others refused to conform to a specific movement, exploring distinct styles and individual philosophies in their writing. This departure from dominant themes like partition and existentialism was marked by novel approaches from writers like Ghazanfer and Musharraf Alam Zauqi, expanding the literary horizons with new themes and concerns.

The emergence of Theatre of the Absurd in Urdu literature is a relatively new and uncommon genre. The first play in this genre, titled “Mazaron Ke Phool” (Graveyard Flowers), was penned and published by Mujtaba Haider Zaidi in December 2008, marking its inception.

The Dichotomy: Classical vs. Popular Literature

In Urdu literature, there’s a longstanding dichotomy between classical literature and popular literature. Classical literature (called “Adab-e-Aaliyah”) has often been esteemed over popular literature (referred to as “Maqbool-e-Aam adab”), which includes works published in digests or magazines, sometimes considered as a “lower caste” by literary circles. However, with modern statistical methods, the vast readership and volume of popular literature can’t be disregarded merely because it doesn’t garner approval from the literary elite. Despite some reluctance among literary critics to acknowledge popular writers, the contributions of figures like Ibn-e-Safi, Humayun Iqbal, Mohiuddin Nawab, Ilyas Sitapuri, MA Rahat, Ishtiaq Ahmed, and numerous others have significantly enriched Urdu literature.

3 comments